BOOK REVIEW: NAPCE Chair Phil Jones on “Beyond Wiping Noses” by Stephen Lane, a New Book on Pastoral Leadership in Schools.

Beyond Wiping Noses – An informed approach to pastoral leadership in schools. Book review.

This new pastoral book written by Stephen Lane (also known as #SputnikSteve on Twitter) was published this month by Crown House Publishing Limited.

It is good to see that a growing interest in pastoral care is resulting in an increased discussion about pastoral issues on social media; more articles and research being presented for publication in journals, including NAPCE’s journal ‘Pastoral Care in Education’ and more books on pastoral topics being published.

The author comments in the book that with the increased focus on mental health and well-being, along with the increase in concerns over cyberbullying and the negative effects of social media, that pastoral care is arguably more important than ever.

This book makes a significant contribution to raising awareness about the contribution effective pastoral care can make to a young person’s educational experience.

It increases understanding about how the pastoral work of the school helps young people to make sense of their education and lives as a member of society.

At the heart of the book is a call for a more informed and evidence-based approach to the organisation and delivery of pastoral care in schools.

It has always been a belief of NAPCE that research informs good practice. In the days before Twitter and the internet, NAPCE was an important forum for members to share good practice and a meeting point for research and debate about good practice.

The book encourages the view that this process is still important even if NAPCE like many other organisations has had to adapt in response to new technology and ways of working.

In many ways the book is a breath of fresh air for NAPCE members and supporters who for many years it seems have been fighting an uphill battle to ensure that pastoral work in schools is valued and recognised for the impact it can have on a young person’s achievement at school and in later life.

The foreword by Mary Myatt recognises the contribution made by the late Michael Marland, who was a founder member of the NAPCE, in raising awareness about the impact of effective pastoral care.

I can remember sitting next to Michael Marland in NAPCE meetings and being aware of his passion and deep-rooted belief that pastoral care was an important part of education.

Unfortunately, that has been challenged in recent years by a focus on examination results and accountability and it is encouraging now that there is a growing awareness about the contribution pastoral work can make to the achievement of young people and this book contributes to this process by developing the readers’ understanding of pastoral issues in schools.

There is a clear structure and organisation to the book with different topics being explored in each chapter in a sensible and balanced way taking advantage of available literature and evidence for each area.

The book provides the reader with guidance on sources of information and resources that can be used to support the planning and delivery of pastoral care in schools.

Each chapter includes a conclusion with a summary of the issues and gives suggestions on how schools and staff working in pastoral roles should respond.

Stephen includes his own thoughts and experience in what he describes as “a reflection of the journey I have taken towards a more informed response to pastoral matters”. (Lane, S. 2020, p5)

There is a focus on secondary schools in the book, which is the author’s own experience, but the issues explored are relevant to professionals working in primary, tertiary and higher education and will develop their understanding and encourage them to reflect on their own policy and practice.

In the introduction the author makes a case for a research-based approach using evidence for the planning and delivery of pastoral care. Stephen comments on how he discovered the NAPCE journal ‘Pastoral Care in Education’.

“immediately I began to see ways to improve my practice in relation to pastoral issues and by extension to improve the experience of the students in my care” (Lane S 2020 p 5.)

In chapter one the book focuses on pastoral roles in schools. It recognises that there can be a lack of clarity about pastoral roles and that they can become reactive and instinctive. He examines the role of the Form Tutor, Head of Year or Middle leader, School Chaplain, School Counsellor and Pastoral Leader in a context where he makes it clear that all adults in a school have a pastoral duty and that pastoral work is not “wiping noses and kicking butts”.

“Napce does a decent job in encapsulating the plethora of particulars involved. It also succeeds I think in traversing the potential false dichotomy between the pastoral and the academic” (Lane S 2020 p 12.)

He recognises that the NAPCE guidance places a strong emphasis on personal development, which is one of the four key areas in the current inspection framework.

He supports the NAPCE guidelines, placing a strong emphasis on the importance of the skills, knowledge and understanding of staff including the suggested requirement that staff;

“Take responsibility for remaining fully informed about developments in pastoral care and in education that have an impact on the support of learners in schools” (Lane S 2020 p13.)

He examines the plans for a designated Senior Lead for Mental Health in Schools and points out the importance of this being properly resourced and given a high status, which is something that all areas of pastoral work in schools would benefit from. The book argues that it is important for schools to have a clear vision for pastoral roles and that this should be used to inform job descriptions.

In chapter two the book asks the question what research can inform the development of pastoral structures and systems and the delivery of effective pastoral care.

“In order to achieve effective pastoral care for the welfare, well-being and overall success of our students and enable them to participate -pastoral leaders must embrace and engage with the current movement in educational discourse towards a research and evidence informed practice”. (Lane, S, 2020 p21).

The author argues the case for policies and procedures and daily practice to be based upon and informed by ongoing critical engagement with research and evidence.

He informs the reader about the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches to research in pastoral care. In examining the difficult task of defining pastoral care the book uses contributions form NAPCE members.

These include Michael Marland and the ideas presented in his 1974 book That introduced the concept of pastoral care being about the ‘crisis of identity faced by adolescents; what do I want to make of myself and what do I have to work with’. (Marland 1974). The book uses the article by a former NAPCE president Ron Best in 2014 which argues that Marland’s book had a significant and long-term impact upon ideas about pastoral care. (Best R 2014.)

“As the founding chair of NAPCE, Marland’s influence should not be underestimated” (Lane, S, 2020p p30)

To explore definitions of Pastoral, the book uses the work of another member of NAPCE’s National Executive Committee , Mike Calvert, who in 2009 pointed out a shift away from the term Pastoral due to its ecclesiastical or agricultural roots and associations with outdated notions of power dependence and models of schooling.

The author points out that even within the pages of the journal – Pastoral Care in Education, it is difficult to locate a clearly recognisable definition. This is a fair comment and reflects the challenges of finding a definition which, from my experience, have been a feature of many discussions and debates at NAPCE’s National Executive and Editorial Board Meetings.

Stephen does respond to the readers’ need for a definition by referring to the first edition of the journal and an article from HMI Eric Lord who provided the following definition;

“the bridge between education and life is best made by those who can help the young to find their way among the exhilarating interests, the satisfactions and the baffling ambiguity of human existence”. (Lord 1983 p 11)

The book also uses a definition from Mike Calvert which he summarises as, “the structures practices and approaches to support the welfare, well-being and development of children and young people”. (Calvert, M, 2009, p267).

It is good to see it recognised in the book, that all the discussions at National Executive, Editorial Board and in the Journal have enabled NAPCE to contribute to developing understanding about pastoral care.

“The NAPCE has its own journal ‘Pastoral Care in Education’ which includes a range of papers on various topics and also publishes special themed issues” (Lane S, 2020, p35)

In chapter three the author argues for the need for a ‘knowledge rich pastoral curriculum’. The book provides examples of organisations and sources for resources that can support schools in planning and delivering a pastoral curriculum.

The chapter explores the various approaches to delivering a pastoral curriculum and questions the messages that are really passed on to young people. An approach is encouraged where schools are clear about what they include in their pastoral curriculum and about the key messages that it gives to learners.

This is important if pastoral leaders are not going to leave it to chance which good habits, moral values, and personal characteristics that the learners in their care pick up.

It is seen a part of the pastoral leaders’ role to make decisions about what should be incorporated into a coherent pastoral curriculum and to be clear about the messages that are given by the hidden curriculum which is defined as the unwritten values, perspectives and beliefs that are transmitted in the classroom and around the school.

The focus in chapter four is on the challenges of preventing bullying. The reader is provided with an overview of literature about bullying in school and recognises the important contribution made by the Journal ‘Pastoral Care in Education’ in developing understanding about this issue to inform policies and practice.

The teacher’s role is explored along with the impact of new technology and in particular social media. The reader is provided with a useful summary of intervention strategies and approaches to prevent bullying in a school setting.

Well-being, and mental health are current concerns for schools and the potential cause of the apparent rise in mental health issues and the role of the school is examined.

The impact the school may have, by the pressure it places on learners to succeed because of the schools need to be accountable for their examination results is highlighted. Once again, the reader is provided with resources and sources of information for raising awareness about mental health issues and planning interventions and support.

The writer suggests that schools can improve learners’ self-esteem and their mental health by ensuring that they have experience of success. This has important implications for how the school provides a positive culture and ethos for learning and supports the personal development of its learners.

In chapter six the book explores different approaches to managing behaviour including controversial topics such as isolation booths. There is a well balanced and sensible discussion about the use of restorative practice to and other strategies that can be used to manage behaviour in schools such as ‘warmstrict’, which is described as a modern manifestation of tough love.

By examining different theoretical and ideological perspectives the writer, makes comments and suggestions that will develop the understanding of pastoral staff and encourage them to reflect on their own procedures and practice.

The reader who is looking for practical guidance is not forgotten and the writer shares ideas about practical steps that can be taken to improve behaviour.

The focus in chapter seven is on the recent interest in what has been called Character Education. Definitions of Character Education are explained and different approaches to implementing it as part of the curriculum are shared with the reader.

The literature is used to explore different approaches to Character Education and the reader is signposted to resources and information There is a recognition that Character Education is a contentious topic and this is highlighted by the writer in exploring the available literature. One suggestion highlighted is that character education is needed in schools because the current school system with its focus on examination results does not fully prepare young people for their future lives.

“They suggest that the current schooling system focused as it is on examination results leaves young people with insufficient resilience and fewer coping strategies that they will need in later life” (Lane S, 2020, p111)

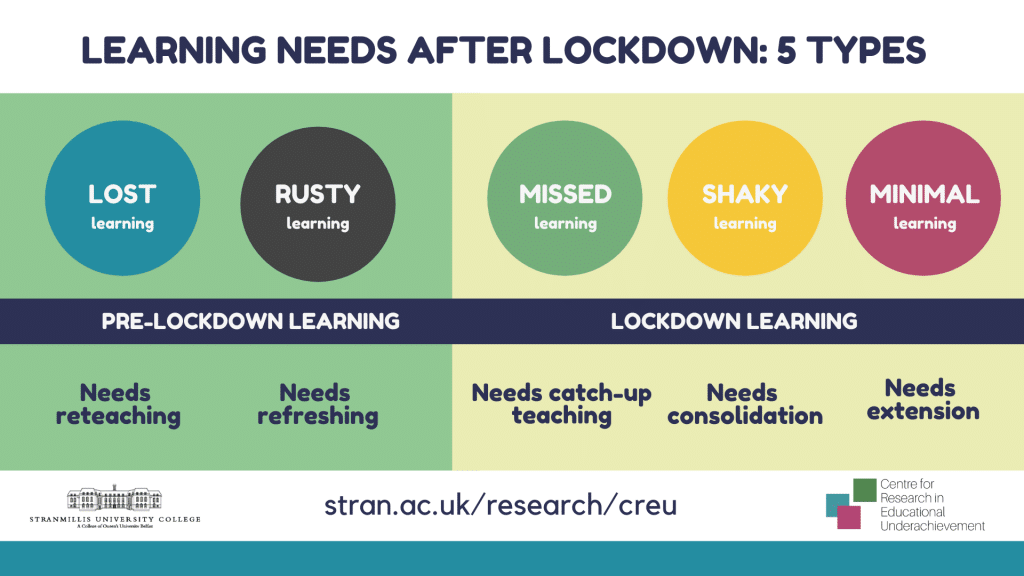

In the next chapter the writer, bravely in my view, tackles the current issue about remote learning during the pandemic. The challenges for schools in the short term are difficult to predict and It is not clear what impact the pandemic will have on learning in the future.

The chapter provides the reader with an opportunity to reflect on the recent experience of schools and what implications this might have in both the short term and long term for young people’s education. There has been increased awareness of the work schools do through their pastoral structures and systems to support young people and look after their well-being.

It is frustrating that a global pandemic was needed before the huge difference pastoral staff make, every day by supporting young people and motivating them to achieve their full potential, was recognised and valued. The writer reports on how schools have continued to take their pastoral obligations seriously and how quickly they have adapted to find new ways to support the learning and well-being of the young people in their care.

The book makes an important contribution to developing understanding about the important impact the pastoral work of the school has on supporting learners on their journey through school and in preparing them for their future roles in society. It makes a clear case for a cohesive pastoral curriculum that is planned, using available evidence and research.

“Teachers must be encouraged to engage in the theoretical and philosophical debate around teaching in order to continually test their practice and so move it towards daily praxis” (Lane, S, 2020, p.126)

This has been the goal for NAPCE since it was first formed in 1982 and this book highlights the important link between research, policy making and practice which has been at the heart of NAPCE’s work for nearly 40 years.

Phil Jones

National Chair

The National Association for Pastoral Care in Education (NAPCE)

References

Best, R. (2014) Forty years of pastoral care: an appraisal of Michael Marland’s seminal book and its significance for pastoral care in schools. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(3): 173-185

Calvert, M. (2009) From ‘pastoral care ‘to ’care’: meanings and practices. Pastoral Care in Education,27(4): 267-277.

Jones, P. (2019) National guidance for pastoral support in schools. NAPCE (3 April). Available at https://www.napce.org.uk/national-guidance-for-pastoral-support-in-schools/.

Lane, S. (2020) Beyond Wiping Noses. Building an informed approach to pastoral leadership in schools, Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing.

Lord, E. (1983) Pastoral care in education: principles and practice. Pastoral Care in Education,1(1):6-11.

Marland, M. (1974) Pastoral Care. London: Heinemann |