ARTICLE: Bridging the Lockdown Learning Gap for Children (Part 2) by NAPCE Officer Noel Purdy

Dr Noel Purdy is a member of the NAPCE National Executive Committee and Director of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement at Stranmillis University College, Belfast.

This article, written by Mr Purdy, is the second in a two-part series focusing on Bridging the Lockdown Learning Gap, following the societal social distancing restrictions because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Bridging the Lockdown Learning Gap (Part Two)

In the first instalment of this blog, I considered two initial questions around the lockdown learning gap: (1) Is there a lockdown learning gap? and (2) What does the lockdown learning gap look like?

In this second instalment, we turn to the third key question: what steps can we take to bridge the lockdown learning gap?

Dr Noel Purdy is Director of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement at Stranmillis University College, Belfast.

BRIDGING THE LEARNING GAP

Over half a century ago, in Education and the Working Class Jackson and Marsden (1966) highlighted a system of educational apartheid in England which benefitted the elite and disadvantaged working class children.

More recently Diane Reay has argued that, despite a common curriculum and many other changes to the educational landscape, ‘educational success is still restricted to a few’ (2017, p.177) and that the winners are predominantly those from families with wealth, influential social networks and a history of educational success.

Reay argues that the upper classes and most of the middle classes have been ‘insulated’ from the last decade of austerity and its consequences, while the working classes have struggled.

Reading the emerging research studies of lockdown learning experiences across the UK (Sutton Trust, 2020; IFS, 2020; Walsh et al., 2020) leaves little doubt that once again children from working class backgrounds with less educated parents are struggling most, with less access to online resources, less time spent learning at home, and less support from their parents.

Once again, it seems, there is no ‘insulation’ for those already disadvantaged in our education system and society at large.

Instead, the social injustice of the lockdown learning gap is striking, and as we consider practical blended strategies to adopt over the coming months of (at best) part-time schooling supported by further home-schooling, we must be mindful that the gap will not be bridged easily or quickly.

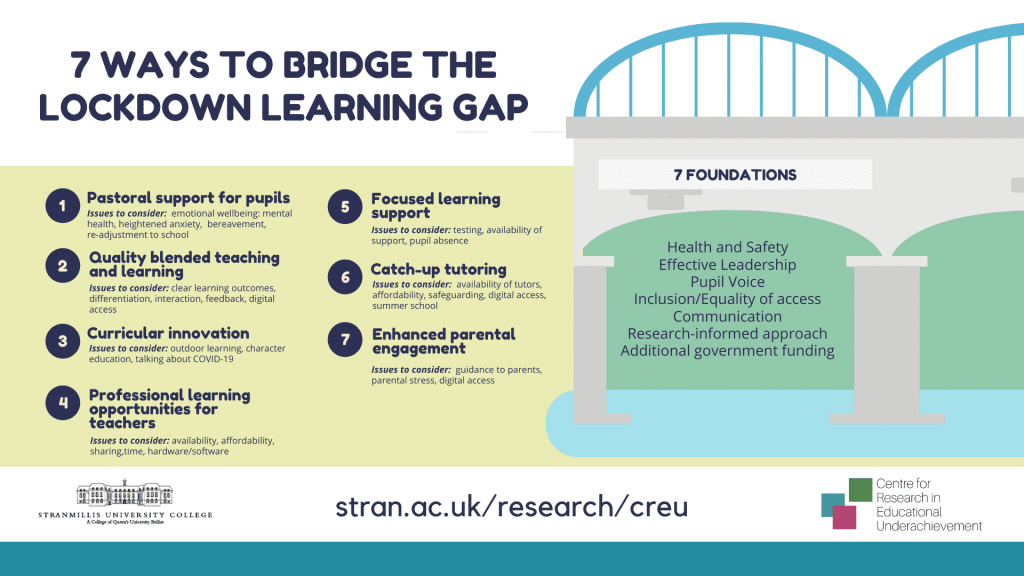

In the figure below, based on a reading of the most recent research, supplemented by my own convictions, and adapted for a new, untested educational landscape, I set out what I see as the seven key ways to bridge the lockdown learning gap, followed by seven underpinning foundations:

PASTORAL SUPPORT FOR PUPILS

The first practical consideration has to be effective pastoral support for pupils all of whom, at the very least, have lived through the crisis of a global pandemic that none of us (as adults) have ever experienced in our lifetimes.

Many will have experienced the uncertainty of their parents being furloughed or losing their jobs, some will have felt the hunger of reduced family incomes and lived off food banks, others will have seen at first hand the devastating effects of COVID-19 and lost loved ones, especially grandparents, and will be experiencing the pain of bereavement.

It must be recognised that many pupils will need emotional reassurance and support, and will feel anxious about leaving home to enter a strangely different, socially distanced school environment.

Schools already have highly-skilled pastoral teams, but they should be prepared to encounter many more emotional health and wellbeing needs in the months to follow, and should adopt a child-centred approach of whole-school understanding and trauma-sensitive ‘flexible consistency’ to ensure that all children feel physically, socially, emotionally and academically safe.

Pastoral care is a feature of every classroom, and all teachers must be encouraged and empowered to show compassion, understanding and sensitivity to children whose experience of lockdown may have been completely at odds with their own.

QUALITY BLENDED TEACHING AND LEARNING

The second priority has to be quality blended teaching and learning. In September it is likely that pupils will be in school at most 50% of the time, so there will still be a need for effective provision of remote learning.

Some teachers naturally feel out of their comfort zones, but I would reassure them that the key elements of effective pedagogy remain the same as before, irrespective of the teaching medium: clear learning intentions, engaging content, differentiated tasks, opportunities for a range of meaningful pupil activities, and timely formative feedback on work submitted.

Our recent report of parents’ experiences of home-schooling in Northern Ireland also revealed that almost a quarter of homes did not have access to a printer. Others were struggling to afford the cost of printer paper and ink. As a result, some schools have already signalled their intention to offer printed hand-outs which is welcome.

Creating online quizzes rather than asking pupils to print pdfs to complete, scan and submit is also something that can reduce inequalities as well as helping to reduce a teacher’s marking load.

CURRICULAR INNOVATION

As my colleagues Dr Sharon Jones and Dr Glenda Walsh have suggested in their recent CREU blogs, there are, thirdly, opportunities for curricular innovation in the post-lockdown learning environment.

While formal changes to the curriculum will take time, teachers can immediately explore the flexibility of the existing curriculum to integrate more outdoor learning play opportunities, to focus on the positive elements of character education within Personal Development and Mutual Understanding (Primary) and Learning for Life and Work (Post-Primary) and, I would argue, to make opportunities to discuss and process children’s experiences of the past six months.

Moreover, there have been some wonderful examples in the past of how school communities have come together in the wake of natural disasters (e.g. Carol Mutch’s work following the 2010-11 New Zealand earthquakes) through creative projects to recount, illustrate or commemorate their own experiences and stories.

PROFESSIONAL LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES FOR TEACHERS

Fourth, teachers have worked hard in challenging circumstances to upskill themselves, but ground-up initiatives like @BlendED_NI illustrate that there remains a skills gap across the profession and an urgent need for Professional Learning Opportunities for Teachers.

The key considerations here are the availability and affordability of such learning opportunities. Stranmillis has recently provided free CPD to over 300 teachers on its Remote Teaching and Learning course (see website for details of all Stranmillis professional development courses).

The other obvious concerns here are teachers’ own access to the internet, availability of appropriate hardware and software, and teachers’ own need to maintain a work-life balance. While there is much to learn from online courses, recent experiences have also illustrated the potential from emerging online ‘communities of practice’ where materials are increasingly shared openly, and much-needed guidance offered by peers.

FOCUSED LEARNING SUPPORT

Fifth, there will be a need for focused learning support for pupils in September. Although pupils are likely to be in school only part-time, it will be important to use some of that time to quickly assess what exactly are the learning needs of the different children in each class, and to consider approaches to support.

For those children on the SEN register, the additional learning and therapeutic support which was often partially or completely absent during lockdown, can be restored but it is important to note that budgets are already incredibly tight in schools and as the 2019 Northern Ireland Affairs Committee inquiry on educational funding highlighted, SEN spending and classroom assistant support are often among the first cuts to be made as school leaders struggle to balance their budgets.

Providing additional focused learning support without additional funding will simply not be possible.

CATCH-UP TUTORING

Sixth, and returning to the opening discussion of the social injustice of lockdown learning, the widest learning gaps to be bridged will require more than skillfully differentiated classroom teaching.

For those children who have been engaged in little or no home learning since 23 March, the challenges of re-entering the educational system cannot be overestimated. In response, there are several options for catch-up tutoring.

One is the summer school model which has been adopted by schools across Harlem Children’s Zone and which endeavours to use vacation time to fast-track the recovery process. Another model is to enlist community volunteers or university students to offer free tutoring to disadvantaged pupils.

The recent EEF report notes that a pre-COVID evaluation of low-cost tutoring provided by third-level students generated a positive impact on pupil learning of three additional months’ progress.

As ever, there are significant challenges in meeting the learning needs of the most disadvantaged children, including demands on teacher time, affordability, safeguarding, and ongoing digital access inequity.

ENHANCED PARENTAL ENGAGEMENT

Finally, enhanced parental engagement: the Stranmillis report on homeschooling during the COVID-19 crisis revealed harrowing experiences by some parents and high levels of stress and exhaustion among others, especially those on the front line employed as Essential or Key Workers.

However, many parents also used the survey to comment on how much they had enjoyed spending time home-schooling with their children, and had felt closer than ever before to their learning. This report should make essential reading for schools as they seek to capitalize on some of the positives from the lockdown.

While parents often requested more guidance on how to support their children’s learning and how to navigate the complex range of learning platforms available, this shouldn’t disguise the fact that they want to be involved and, coming out of lockdown, I would contend that this is an opportunity for schools to build on, improving communication with home, welcoming dialogue and embracing the notion of parents as learning partners.

A FURTHER SEVEN FOUNDATIONS TO BRIDGE THE LOCKDOWN LEARNING GAP

While these are important practical steps to be taken, the figure illustrates a further seven foundations upon which the bridge must be built.

Of foremost importance, of course, is the health and safety of the entire school community (pupils, all staff, parents, visitors) and it goes without saying that schools must follow the most recent government guidance on social distancing, PPE, hand sanitizing etc. as there are very real and justifiable concerns that a return to school as part of a broader easement of lockdown restrictions could lead to a rise in the R number, as was briefly the case in Denmark following the re-opening of schools there on 15 April.

Throughout this crisis we have seen excellent examples of effective school leadership, with gifted principals taking difficult decisions with little guidance to help them, communicating regularly, informing and reassuring the school community.

Given the unique circumstances of each school, school leaders will continue to need to adapt broad-stroke guidance to their individual school circumstances. The underlying principles of pupil voice and inclusion/equality of access remain prime considerations to ensure that pupils are involved meaningfully and have a valuable role to play in their schools, and that no one is left behind or excluded, willfully or by oversight.

Regular, clear and consistent communication at and between all levels has also emerged as a much valued element of a school’s response to a crisis. I would argue that this will be particularly important in the approach to the new academic year, when staff and pupils will naturally be feeling anxious about the return to school, though not to school as they knew it.

With technological support, it will be possible to communicate directly to pupils and parents, showing them (via photos and/or video) what schools and classrooms will look like, thus alleviating some of the understandable anxiety that is already growing. Adopting a research-informed approach is also more important now than ever for educators.

If the current health crisis has shown anything, it is that the scientific community has united as never before, sharing expertise, making research open-access, adapting as new findings emerge and helping to inform those charged with making policy decisions.

There is an onus on those of us who are researchers to work hard to disseminate our findings to policy-makers and to those on the front line in schools. All of this requires generous government funding if it is to become a reality rather than an aspiration, at the very time when budgets look to be tighter than ever before. However, this pandemic has demonstrated that there is the potential for additional spending where the need is deemed to be great enough. So why not now?

Is this not the moment to invest in educational recovery, to facilitate the purchase of the latest technology (hardware, software, internet access, printers) to enable effective blended learning, to support the efforts of schools to upskill staff through high-quality professional development, and to provide learning support to those in danger of being educationally as well as socially ‘left behind’?

There is no quick fix, no silver bullet. Bridging the lockdown learning gap will require vision, courage, tenacity, skill and investment. It is time to get started.

Noel Purdy

Member of the NAPCE National Executive Committee & Director of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement at Stranmillis University College, Belfast. |